Only one Wabash Valley Tapscott,

Wesley “Tabscott” [31 Oct 2015 post], served in the American Civil War, but some

Clark County families into which the Tapscotts married played much larger roles.

One was the Lowrys.

Towards the end of the War, on 15

Feb 1865, Jackson Lowry, husband of Eliza Ann Sweet [27 Sep 2015], was mustered

into Company C of the 155th Illinois Infantry, a most unusual action for

a 45-year-old married man with seven children. The 155th was

assigned to duty in Tennessee, guarding the Nashville and Chattanooga railroad.

By the time the regiment was disbanded, on 4 Sep 1865, it had lost seventy-one

men to disease, but not a single one to military action. Jackson's decision to enlist may be due to the actions and fates of two of his sons.

|

Battle of the

Wilderness (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division).

|

Much earlier, on 5 Sep 1861, Jackson

Lowry’s oldest child, Henry Patrick had mustered into the 25th

Illinois Infantry, Company D. Henry was with General Grant at the start of his 1864

Overland Campaign to force rebel forces from Virginia. After crossing the

Rapidan River, Union Forces fought a bitter battle with Lee's army on May 5

through 7 across the Wilderness of Spotsylvania, an area crisscrossed by small

streams and covered with heavy underbrush. The three-day battle resulted in

29,800 casualties out of 162,920 men engaged. In the days to come, Grant would fight in the Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse, the Battle of North Anna, and the Battle of Cold Harbor. At some point around this time, Henry was struck by a rebel shell. The date recorded for the injury, 23 Jun 1864, is over a week after the conclusion of the last (Cold Harbor) engagement. Henry's niece claimed that the injury occurred during the Battle of the Wilderness. Of course records of injuries during war are often incorrect. Henry survived, although years

later his shoulder still bothered him.

But the Lowry who suffered most from the War was Jackson’s son Lewis Taylor. Military men often overlooked the age requirement of eighteen for enlistment. As many as one-fifth of Civil War soldiers were below the minimum age. Lewis was one of those. On 30 Mar 1864, at age 15, he mustered

into Company I, 54th Illinois Infantry in Mattoon, Illinois. Just two days earlier, a gang of "Copperheads" had attacked some members of the regiment in Charleston, Illinois, killing an officer and four privates. Lewis's story has been recorded by his daughter Mary Elizabeth (Lowry)

Johansen in her book The Merry Cricket

[29 Sep 2015]:

[Lewis] enlisted in

Mattoon, Illinois, and was sent with hundreds of other young recruits to join

General Sherman on his march to the sea. However, before his unit could reach

the army in Georgia, news was received that Savannah had fallen. The city was a

sea of flames, the campaign in Georgia had been a complete success, and there

was much rejoicing throughout the North. But until someone could decide where

father's unit should be sent next, it was ordered to stay encamped right where

it was.

The green recruits

from Illinois were glad to have the chance to rest up. They were led by

officers as inexperienced as the men themselves. None of them had been trained

in the techniques of war. So, although deep in enemy territory, they lit their

campfires and relaxed, all unaware that they had attracted the attention of

strong rebel bands which closed in on them easily and which captured the entire

unit before it had a chance to resist.

“It was a long march

from there to Andersonville,” father said, remembering, but not with

bitterness. “Many of the boys who were guarding us were farm boys like

ourselves. When their officers were not listening they'd be friendly as could

be. What was it like farming up North, they would ask, and what would us

Yankees do after Lee had licked us?”

He smiled. “But we

changed our minds about them when we finally got to Andersonville. We'd heard

about it. The stories had gotten around. But even the worst we'd heard didn't

come up to what we found. It was much more than just the most awful

filth-infested pest-hold anyone could ever imagine.”

“It was a place

where Southern men, and boys, encouraged by the example of the worst bullies

amongst them, lost whatever sense of decency they might have been born with and

just let themselves have fun being inhuman, not just jailers but murder-loving

fiends ! Only a person willing to give up acting like a man could treat other

men like animals instead of like human beings.”

“The food was always

spoiled, the bread moldy, the soup soured. There was never anything to drink

except water and there was just one water spout. This was out in the courtyard

and there was a low, stone wall all around it. A prisoner who was thirsty, even

those who were sick, had to crawl to this watering trough. But if anyone poked

his head up too high over this wall, he was shot at by the guards. Many

prisoners, crazed. by thirst, or the pain of their wounds-men whose spirits had

been broken or who had given up all hope-deliberately chose this way out.”

“Wirz was hanged for

his brutality, his inhuman treatment of the Union prisoners at Andersonville.

But he'll be hanged over and over and over again so long as there is anyone

left to remember him!”

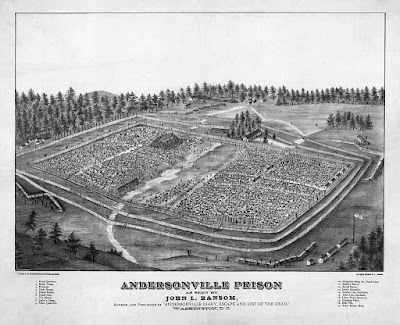

|

| Andersonville (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division). |

Lewis, who mustered out in Little Rock, Arkansas, on 15 Oct 1865, was a survivor. Of the 45,000 Union soldiers

confined at Andersonville, nearly 13,000 died at the prison. The prison commandant,

Captain Henry Wirz, was the only person to be

executed for war crimes during the Civil War.

There is one bothersome problem

about Lewis Lowry’s story. Lewis’s name does not appear in lists of

Andersonville prisoners. Nevertheless, his story is probably true. Present day

prisoner lists are compiled from various sources and are known to have errors. Lewis

is known to have served in the Civil War and the details of his story appear to be correct.

No comments:

Post a Comment

To directly contact the author, email retapscott@comcast.net